Breed History

“To become well acquainted with the true Akitainu, one must diligently study the history of the development of the Akitainu from the ancient to modern times. In this way, one will be able to appreciate the temperament, character, and be able to visualize the true Akitainu.”

— Author and AKIHO judge and boardmember

Naoto Kajiwara (1913-2000)

“My Thoughts on the Akitainu”. Aiken Journal. Tokyo: Shin Journal-sha, 1975

History of the Akitainu: A Summary

Many westerners will have first learned of the Akitainu from the inspirational stories of loyal Chūken Hachiko who waited at the train station for his owner Professor Hidesaburō Ueno to return, or Kamikaze and Kenzan, the two Akitainu that were given as gifts to Helen Keller. Other stories about the breed reflect a sense of orientalist tropes, and like many tall tales, they have developed well beyond their historical accuracy. Myths and misinformation surrounding the Akitainu have been perpetuated in the west for decades. Two newer examples of such incorrect information currently circulating on social media include:

- The Japanese believe a samurai is reincarnated as an Akitainu (or vice-versa)

- There is a famous Japanese proverb: “Gentle as a kitten (or geisha); fierce as a samurai”

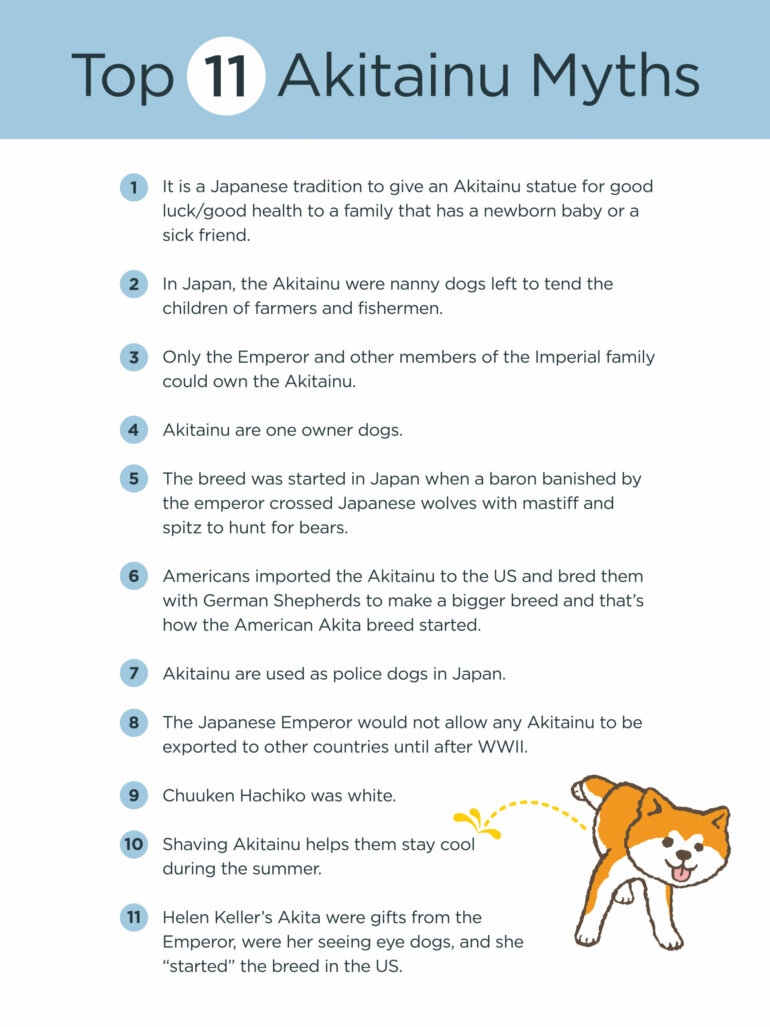

While the above examples are too ridiculous to be taken seriously, the exact beginnings of other misinformation, as depicted in our Top 11 Akitainu Myths graphic (see the bottom of the page), are difficult to trace, but they are mainly perpetuated in the writings of westerners, and perhaps suprisingly not in the publications of reliable source material written by Japanese historians and breed experts.

What follows is a summary of Akitainu breed history based on country of origin sources.

Over time, we hope to add more Japanese articles in translation to this page.

Part I. In the beginning there were the Matagi and their dogs

The Matagi of northern Japan are hunters who have existed for hundreds of years and are said to be descendants of the indigenous Ainu of Tōhoku, Hokkaido and Sakhalin (Karafuto). There is a spirituality and reverence of nature attached to the ways of the Matagi who observe ritual prayers, chants and offerings prior to entering the rural mountain landscape or embarking on a hunt, as well as during and after a hunt. One such ritual occurs upon the slaying of a bear in which a symbolic ceremony is performed to guide the bear’s spirit back to its divine ancestors. The Matagi utilized their hounds, Matagiinu, to track and bay bear, boar and deer. The Matagiinu was a medium-sized hunting dog with stand-up ears and a curled tail and is considered the ancestor of the modern Akita breeds; both breeds of Akita (the Japanese Akitainu and the American Akita) share the same origins in these regional landrace hunting dogs.

A Matagi and his dogs

Note that the size and bone of these Matagiinu are quite different from the Akita fighting dog. Photo from Okada Mutsuo’s Photo Collection of Old Nihonken.

Hunting with Akita Matagiinu

Photo from March 1936 issue of Matagiinu Journal of the Ryouken Akitainu Kyoukai.

Part II. The haves, the have nots, foreign breeds, fighting dogs

Towards the end of the Edo Era (1603-1867), also known as the Tokugawa Shogunate Era, civil unrest in the Dewa region (Akita Domain) resulted in peasant uprisings. Consequently, the nobility and those in the upper end of the socio-economic strata began using the local dogs to guard their property and domiciles. The then medium-size Matagiinu were bred towards a larger and more imposing size to fill this new role. Although dogfighting in Japan had been recorded as early as the 1300s, it became popular in the Akita Domain especially among the warrior class until it was eventually banned in 1907. Despite the illegalization of organized dogfights, however, they were still held in rural areas, such as Ōdate. As Japan opened its economy to trade with Europeans, western breeds were imported and grew in popularity.

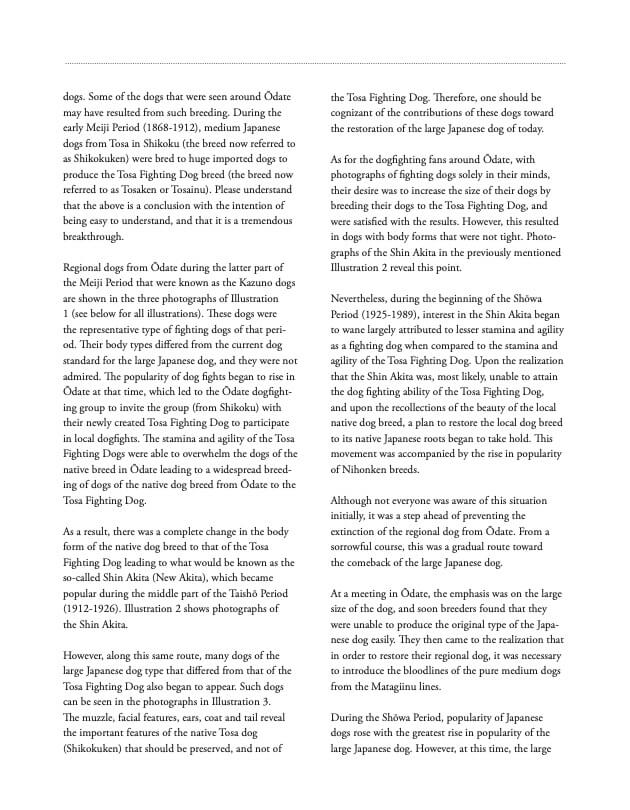

During the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō (1912-1926) periods, in order to increase size for the purposes of guarding property and dogfighting, the Matagiinu had been mixed with the Tosa Fighting Dog, itself a mix of Shikokuken and foreign breeds such as St. Bernard, Great Dane, Mastiff, Bull Terrier, Pointer, etc. The dogs of the Akita region crossbred specifically for dogfighting were known as Shin Akitainu (translation: new Akita dog).

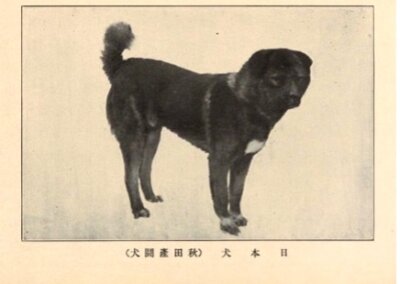

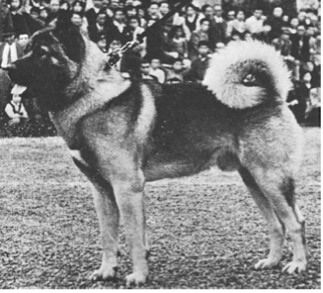

Gamata Go (Dateisami Go), Champion Akita Fighting Dog (Shin Akita)

Champion Akita Fighting Dog (Shin Akita) Gamata Go (Dateisami Go); it is believed the first Tennen Kinenbutsu Kingō Go comes from the maternal line of this dog.

Akita no Touken (Fighting Dog of Akita)

Akita Fighting Dog of the Meiji era (touken means fighting dog). The Akita Matagiinu (hunting dog) were mixed with western breeds and began to lose its Nihonken morphology.

Tosa Fighting Dog

The Tosa Fighting Dog was a mix of the Tosa (Shikokuken) and western breeds. Such dogs were further crossed with the Akita Matagiinu. This photo is from 1918.

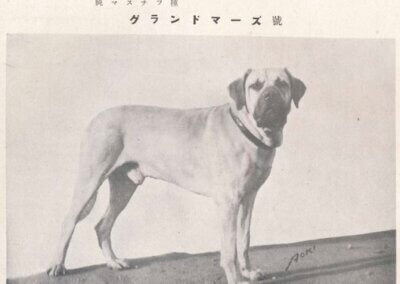

Mastiff stud advert

Mastiffs were mixed with local dogs from Kochi to create Tosa Fighting Dog which were crossed with Akita Matagiinu.

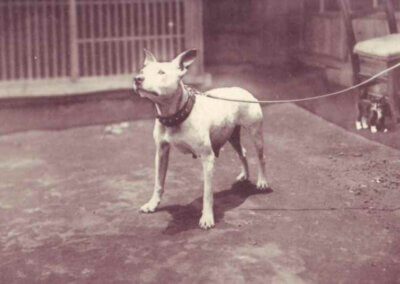

Pesi the Bull Terrier

Bull Terriers such as this one born in 1881 were mixed with regional native dogs to improve fighting dogs.

St. Bernard (Yui family)

The majority of Japanese breed history writers corroborate that the St. Bernard was a breed mixed with the Matagi Akitainu for larger size in the touken ring.

Part III. Calls for preservation in the Meiji (1868-1912) and Taishō (1912-1926) Eras

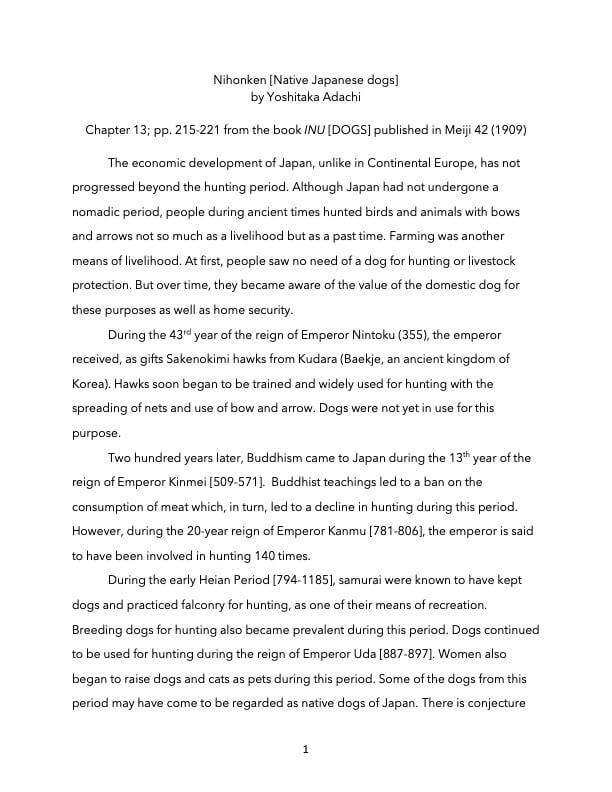

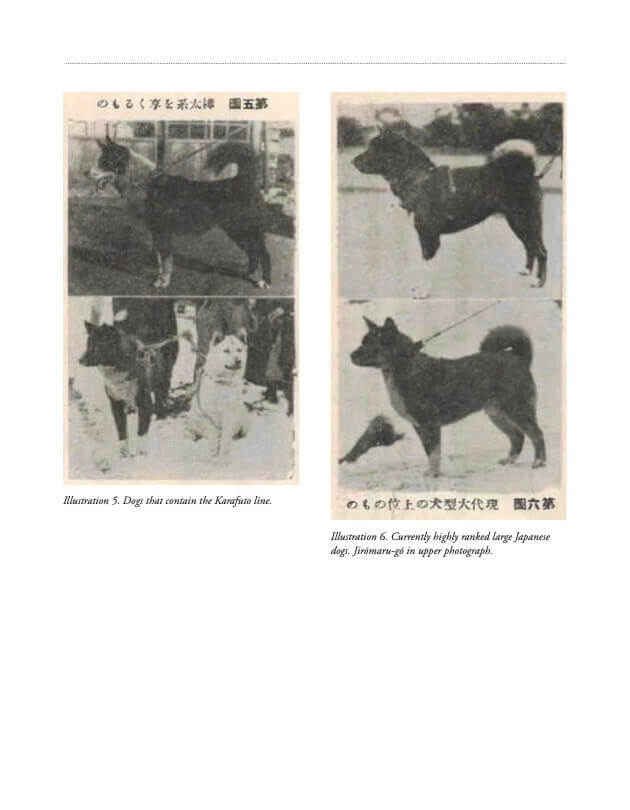

By the early 1900s, Japanese academics, government agricultural officials and some breeders felt that the so-called Shin Akitainu had lost its Nihonken (native Japanese dog) characteristics. Influenced by a wave of nationalism and a growing desire to preserve the native dogs, breeders were encouraged to breed away from the foreign dog appearance (drop ears, hanging tails, black mask, wrinkled heads, round eyes, loose lips and skin on the face, dewlaps, corpulent body structure, extra-large size, etc.) and back to the Nihonken morphology. There is even a chapter titled “Nihonken” by Yoshitaka Adachi in a book titled Inu (written before 1904; published in 1909) recommending the restoration of the Nihonken with illustrations depicting the differences between an Akita hunting dog and an Akita fighting dog. Efforts to restore the regional Akita dog slowly began at this time as breeders re-introduced large and large-medium Nihonken bloodlines of hunting dogs found in Matagi villages, Karafutoken from Karafuto (now Sakhalin, Russia), Tōhoku, and Hokkaido, as well as medium-size Nihonken.

Akita Hunting Dog of the early 1900s

This illustration is from a chapter called Nihonken in a book called Inu (1909) in which the author Mr. Adachi urged breeders to preserve the Akita Hunting Dog.

Part IV. The formation of preservation societies and the first restoration period

In 1927, the Akitainu Hozonkai (AKIHO), translated as the Akita Dog Preservation Society, was established in Ōdate, Akita Prefecture. It was the first time the breed’s name was officially used by a preservation organization. In 1928, Nihonken Hozonkai (NIPPO), translated as the Japanese Dog Preservation Society, was established in Tokyo. NIPPO originally classified the native dogs by size—small, medium and large—and not by breed; therefore, dogs of different sizes were sometimes crossbred. Crossbreeding the various Nihonken at the time was an acceptable practice to restore and preserve the Japanese-type dog. It wasn’t until decades later when NIPPO began to use breed names.

The current remaining Nihonken breeds categorized by size are:

- Small – Shibainu

- Medium – Hokkaidoken, Kaiken, Kishuken and Shikokuken

- Large – Akitainu

In a 1937 issue of NIPPO’s journal, dog breeder, Nihonken expert and advisor to NIPPO and AKIHO, Mr. Hyoemon Kyouno published an article regarding the restoration of the large Japanese dog which states that in the 1930s, Hokkaidoken and Karafutoken (Sakhalin Husky) bloodlines were documented as being part of the breeding programs of some Akitainu kennels. Furthermore, Mr. Shoichiro Miyamoto says in a separate article that Hokkaidoken from Hidaka and Iwateken (a native breed from Iwate Prefecture in Tōhoku that sadly no longer exists) were also bred with the Akitainu. Moreover, at least one old Akitainu pedigree is known to contain Kaiken. According to breed historian Mr. Naoto Kajiwara in the book Akita published by the Japan Kennel Club, NIPPO held annual exhibitions from 1932 until 1942 where Akitainu were exhibited in the large Nihonken category. He further writes: “Their ancestry included Hokkaido and Kishu lines. There is an indication that even then Japanese dogs such as Matagiinu were used for crossbreeding” (46). While it may not have been a rampant practice to mix the different sized Nihonken, it was deemed a necessary and acceptable practice to restore the native dogs. It seems the medium-size Nihonken were considered closer to the ideal of the native dog as a reflection of the natural beauty of Japan by NIPPO leaders.

It is common knowledge that the Japanese government forced citizens to surrender non-military dogs for food and clothing during World War II. Military-trained dogs such as German Shepherds were exempt from confiscation. Although in some areas registered hunting dogs and natural monument breeds were said to be exempt, the Akitainu (as well as other native breeds) was in danger, and restoration efforts were interrupted. Mr. Morie Sawataishi, along with several other dog men in northern Japan, were said to have secured their Akitainu in rural mountain villages with Matagi and farmers. A few allegedly bred their Akitainu with German Shepherds, and some US military were rumored to have bred their own military German Shepherds with Akitainu. Such mixes were added to the very small Akitainu population that survived the war. Mr. Kajiwara in Akita listed the names of just 18 pure Akitainu documented by Mr. Kyouno as having survived WWII (in other accounts the numbers are fewer).

Part V. Post-WWII era and the second restoration period

Following the war, AKIHO, still headquartered in Ōdate, began anew their efforts to restore the breed. An offshoot organization called Akitainu Kyokai (AKIKYO) was founded in 1948 in Tokyo. In the early days of AKIKYO, the organizations collaborated and in the immediate aftermath of the war, AKIHO, AKIKYO and NIPPO continued their efforts to eliminate the western breed influence and restore the Akitainu. There were other Akitainu organizations that came and went, but the two most influential were AKIKYO and AKIHO (AKIKYO was disbanded in 2013 leaving AKIHO as the first and last remaining Akitainu organization in the country of origin). For decades, it was common for owners and breeders to enter their dogs in the AKIHO, AKIKYO and NIPPO exhibition rings. It is in the post-WWII era when the most uninterrupted progress was made in the restoration of the Akitainu according to the Japanese vision.

In the 1950s, Americans had begun importing descendants of Kongo Go Heirakudo Kensha of the famous Dewa line to the US. While Kongo Go was considered a fine example of the transitional large Akitainu for his time, even his own breeders, the Hiraizumis, were critical of the influence of Kongo Go’s features (e.g., black mask, loose skin, corpulent body, etc.) on dogs of the era. After several years of visits to the US by Dr. Keiichi Ogasawara and other Akitainu Hozonkai officials, the very first overseas branch of AKIHO was officially established in Los Angeles in 1970. The original membership of AKIHO North America included Japanese immigrants and Japanese Americans as well as members of the Akita Club of America. AKIHO correspondence and documents received from Japan were translated into English by Japanese-speaking members of the branch. The translations were important for breeders in the US to understand the goals set for the breed according to the direction of the country of origin. In addition to having access to these important translated documents, some American Akita breeders attended AKIHO shows in Japan with regularity so that they could see for themselves the Akitainu breed in its home country. It was clear even then that the Akitainu being shown and bred in Japan were very different from those bred and shown by early AKC fanciers in the US. In fact, in 1970, Mr. Ryonosuke Hiraizumi himself gave a presentation to American enthusiasts in Los Angeles and conveyed why Kongo Go’s type must not be perpetuated in the Akitainu. To the Japanese, the Dewa line did not reflect the ideal Nihonken type, which is why the Dewa line was proactively bred to Akitainu lines that fit closer to their idea of the standard such as the Ichinoseki, Akita Nikkei, Taihei and other lines to restore the breed.

Aikuni (Aikoku) Go Akita Echizen Shi

Aikuni Go Akita Echizen Shi was born in 1932 and was instrumental in the restoration of the Akitainu.

Dog from Sakhalin

Karafutoken (sometimes debatably referred to as Sakhalin Husky or Sakhalin Laika) lines were re-introduced to Akitainu.

Samoyed-type Karafutoken

An example of Karafutoken/Sakhalin Husky. Such dogs are said to be where the long coat gene comes from in the Akitainu.

Koma Go Banko, photo from 1939

Midsize Nihonken such as this one possessed the elegant urajiro and omotejiro that the large transitional dogs had lost from being mixed with western breeds.

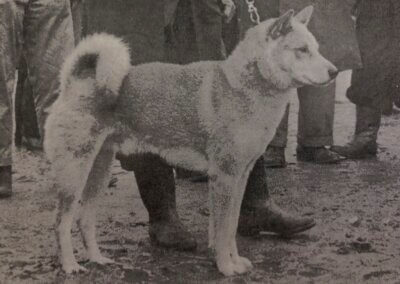

Hatsukaze Go

The midsize Nihonken were considered good examples of the native Japanese dogs and were bred with transitional large dogs to restore the Akitainu.

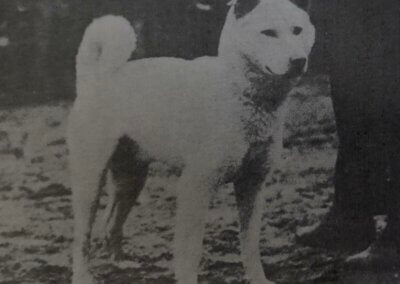

Anko Go Hokkaido Shimazawa

An example of a mid-sized Nihonken from Hokkaido in 1934 (such dogs would later become known as the Hokkaidoken breed).

Goro Go

Goro Go was born in 1934 and reputed to be the grandson of the famous Chūken Hachiko (most likely just a rumor).

Kantorajo Go Heirakudo

This female is a fine example of Akitainu restoration prior to WWII. Photo was taken in 1937. Interestingly, she came from the same kennel as Kongo Go.

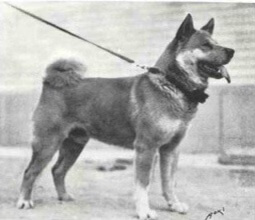

Kongo Go Heirakudo

Born in 1947, Kongo Go of the Dewa line was considered a great transitional Akita of his time despite flaws inherited from the breed mixing of the fighting dog era. He became a popular sire as his owner was an able promoter/salesman.

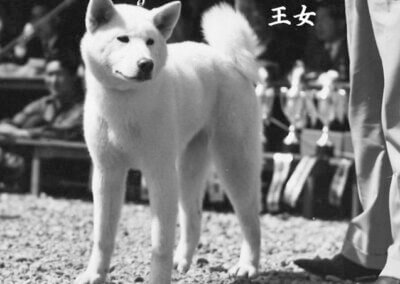

Red female Akitainu

An entrant at the 1970 AKIHO Headquarter Exhibition. By this time, Japanese breeders regarded the US to be 20 years behind in restoring the Akitainu.

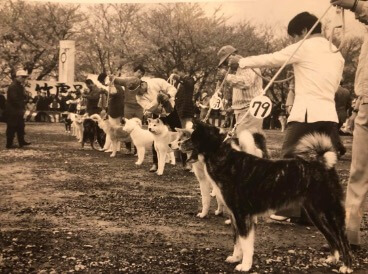

AKIHO show in Japan

Akitainu Hozonkai exhibition in Japan in the 1970s. Members of AKIKYO and NIPPO played a part in the restoration of the Akitainu, but over time, AKIHO may be considered the most influential preservation society for the breed.

Photos of the medium-size native Japanese dogs are offerings from Nihonken Hozonkai’s photobook collection and published with their permission.

Part VI. When one becomes two (or why there are two breeds)

By the time the Akita was recognized by the AKC in 1973, the Japanese breeders and judges who visited the US in years prior, including Kongo Go’s breeder Mr. Hiraizumi, had already been warning that a split would be inevitable because the Americans continued breeding dogs that were of the transitional Akita type and not what the country of origin considered to be the Akitainu. The Americans, mainly those who were not of Japanese descent, preferred the transitional large dog and continued to develop what would eventually become known throughout the world as the American Akita.

The majority of kennel clubs in the world are affiliated with the Fédération Cynologique Internationale (FCI). For most breeds, the FCI follows the country of origin. When Akita exhibitors in Latin America grew frustrated in the conformation ring at their inability to win with their transitional large Japanese dogs under the country-of-origin standard, they began voicing their displeasure. The JKC and FCI set in motion a series of meetings with fanciers from all over the world until a solution was found. The breed was split by the FCI in 1999. The agreement established Japan as the country of origin of both breeds and the US as the country of development for the American Akita.

In 1997, some members of AKIHO North America had founded the Japanese Akitainu Club of America (JACA) in the eventuality that the AKC would recognize the breed reflecting the ideal Nihonken type with respect to its country of origin. In 2020, the AKC accepted the Japanese Akitainu into its Foundation Stock Services—the same year that AKIHO North America celebrated its 50th anniversary (the breed will be moved to Miscellaneous Class in 2023).

Now, the world has two Akita breeds. If we consider what the preservationist Japanese Akitainu and American Akita breeders have accomplished over the years, one can appreciate the vision and effort it took for each breed community to have come this far. When stewards of the breeds learn the factual history which includes the various breeds that are a part of the modern Japanese Akitainu and American Akita, it becomes obvious that declaring one or the other as resembling the “original” Akitainu is a moot point and does a grave disservice to the decades of hard work and determination of breeders involved in the restoration of the Akitainu and to the development of the American Akita.

As breed historians continue their research of Japanese documents and uncover new information, our understanding of the history of the Akitainu may be updated. New information, as it becomes available, will be added to this article.

References

70th Anniversary Nihonken Shashin-shu. Nihonken Hozonkai. Tokyo: April 1998.

Adachi, Yoshitaka. “Nihonken.” Inu. Tokyo: Dai Nihon Nokai Hakko, 1909. 215-221.

Hiraizumi, Ryonosuke. “The First Los Angeles Branch Show 1970 and the Akitainu in the United States.” Akitainu Journal. Ōdate: Akitainu Hozonkai.

Kajiwara, Naoto and the Japan Kennel Club. Akita. Tokyo: Japan, Japan Kennel Club, Inc., 1998.

Miyamoto, Shoichiro. “A History of The Akitainu from Prehistoric to Current Status.” Aiken Journal. Tokyo: Shin-journal-sha, March 1961. 70-72.

Okada, Mutsuo. Ōko Nihonken Shashin-Shū (Old Japanese Dog Photobook). Tokyo: Seibundo Shinkosha, 2002.

JACA would like to thank Akitainu Hozonkai headquarters in Japan, AKIHO North America, Nihonken Hozonkai, Tatsuo Kimura, and Mr. Stein for their contributions of photos and articles referenced on this page. Some photos sourced from Empire Dogs blog.

Additional reading for Akitainu history enthusiasts

A few articles from Japanese publications to English translation may be found in this section.

This chapter called “Nihonken” by Yoshitaka Adachi in the book Inu is possibly one of the oldest writings on record urging Japanese breeders to preserve the native breeds. Composed prior to 1904 but published in 1909, Adachi mentions the Akita hunting dog and the Akita fighting dog specifically.

Translator Tatsuo Kimura found this article by Shoichiro Miyamoto a challenging task due to the writing style of the author. Miyamoto was a hunter and something of a businessman and promoter of his kennel and various clubs moreso than a writer.

The article that follows by Hyouemon Kyouno was first published in 1937. Mr. Kyouno came from a prominent landowner family in the sake and kimono trades in Akita Prefecture. He initially bred Tosa Fighting Dogs and Shin Akita but went on to become a judge and advisor, and held board positions in preservation societies. His Akita Nikkei line played a significant role in the restoration of the Akitainu breed.

The following article about the Karafutoken by Dr. Tetsuo Inukai (1953) was shared with us in its original Japanese language by a member of AKIHO Russia. The influence of the Karafutoken on the Akitainu must not be minimized or overlooked so we are happy to feature the article here. As always, we are grateful for the opportunity to collaborate with our overseas friends and to our learned and respected friend Dr. Kimura for his hard work and dedication. This English translation was first published in JACA’s quarterly newsletter Wan Wan in spring of 2023.

A bit of historical context: The AKC recognized what the Japanese considered to be the transitional Akita in 1973 and closed the studbooks to imported Akitainu registered to AKIHO, AKIKYO and NIPPO. By this time in Japan, great strides had already been made in the restoration and refinement of the Akitainu. Our thanks to our sister club Akitainu Hozonkai North America and Dr. Tatsuo Kimura for granting us permission to publish the following article.

All photos and content on this page are for educational purposes only.